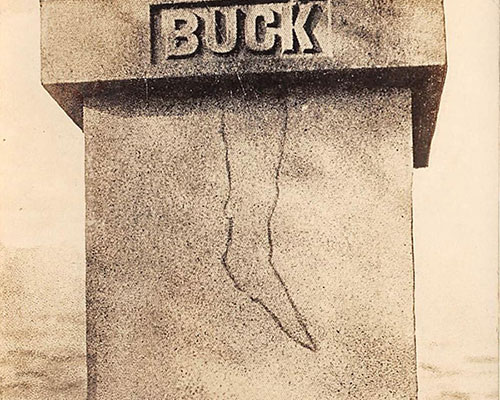

A mysterious leg is indelibly stained on the face of the monument to Colonel Jonathan Buck of Haverhill. (Photograph from historical postcard.)

By David Goudsward

Special to Wavelengths

The image is well known – the image of a leg indelibly stained on the face of the monument to Colonel Jonathan Buck—a Haverhillite rejected by his hometown, but who found success founding a town in Maine.

As with every good ghost yarn, there are various incarnations of the story. Some say it was a visual reminder of the curse levied by a local witch burned alive by the pitiless judge and founder of Buckstown, Maine. Others state Colonel Buck had a mistress, who once her beauty faded, was tossed aside for a younger paramour. When the original mistress started raising a fuss, Buck had her arrested for witchcraft.

In all versions, there is a very unhappy woman about to be burned at the stake who places a curse upon the Colonel, warning she would haunt his grave.

Some versions have her proclaiming she would “dance upon his grave” at his death. Others have her flame-broiled leg falling out of the fire where her deformed son, rejected by the community, and secretly Buck’s illegitimate child, grabs the leg and flees into the wilderness.

The earliest known record of the story appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer Sunday, July 17, 1898, but the tale had been developing locally for a half century. This was the golden age of the grand hotels of the White Mountains and undoubtedly an intrepid Philadelphian, continuing up into Maine to view the scenic vistas and forests primeval, ran across the legend. Various newspapers picked up the story from the Inquirer. Eight months later, one of those newspapers was the Haverhill Gazette. The Gazette article became the standard version, both because of how widely the Gazette was distributed in her Queen Slipper City glory days, and because the story involved a Haverhill boy.

Rejected in Haverhill, Buck Drives Maine Colony

Buck Memorial Library was a gift from the family of Richard Buck, a descendant of Jonathan Buck.

The Bucks arrived in Haverhill in 1722 when Jonathan was 3 years old. He grew up in Haverhill and married a local woman. His nine children were all born in Haverhill—six survived to marry in the town, firmly establishing the Bucks as members of the community. By 1759 however, Jonathan Buck was growing unhappy with restrictions being imposed by the Haverhill Proprietors. His request to construct a shipyard on Water Street where Mill Brook entered the Merrimack was refused and instead he was offered privileges on Mill Brook for the same parcel. It was an empty gesture – Buck didn’t own the parcel on the west side of the brook, making the construction of a mill dubious at best without buying out his neighbor.

In July, 1762, he gave up on trying to thrive in Haverhill. He sailed on the sloop “Sally” up the Penobscot River as part of a team surveying six new plantations granted by the Massachusetts General Court to Deacon David Marsh of Haverhill and 351 others. In June, 1763, Buck came back to settle at what had been designated Plantation No. 1. Almost immediately, he became the driving force in the colony, building the first sawmill and a store.

Trouble came with the Revolutionary War, the British military built Fort George at Castine, effectively controlling Penobscot Bay and cutting off trade along the river. As a 60-year-old, Buck took part in the disastrous Penobscot Expedition to lay siege to Fort George. With most of Plantation No. 1 deserted, the 16-gun Royal Navy sloop HMS Nautilus sailed into the plantation’s harbor and the crew retaliated by burning the town. His colony in ashes, Buck walked the 200 miles from Bucksport to Haverhill to stay with his sons in Haverhill. When the war ended in 1783, Plantation No. 1 was resettled and renamed Buckstown Plantation. As Jonathan Buck’s health began to fail, the town was renamed again, now simply called Buckstown to further honor their founder.

Jonathan Buck died March 18, 1795, a local war hero, a successful businessman and beloved town founder. He was buried in the Buck family cemetery. The location on modern maps is just east of the junction of Highway 15 and U.S. Highway 1. The 1759 denial of Buck’s request for shipbuilding in Haverhill became ironic as shipbuilding became the principal occupation in Buckstown, so much so that the town was renamed Bucksport in 1817 to reflect the growing importance of the docks.

In any other case, this would be the end of the story. Local founder, buried in his family grave, destined to be a figure in the local history books. In this case, the story was just beginning. In August of 1852, Jonathan Buck’s great-grandchildren decided the town founder needed a more appropriately impressive memorial. They erected a granite obelisk to him, situating in a prominent corner of the graveyard where it could be seen by passersby (Buck himself was actually buried 15 feet away).

Paranormal ‘Curse’ Rewrites Buck’s Legacy

As the monument began to weather, a stain appeared in the granite, directly below the Buck name. Pareidolia, the psychological term for seeing patterns and images where there aren’t any, kicked in at full force. The stain became the image of a woman’s leg and foot. And where’s there’s a mysterious image, there must be an explanation. Stories began to circulate as to why it had appeared and remained after several attempts to remove it.

The kin of Colonel Buck may have guaranteed his immortality by raising the memorial obelisk, but it worked at the cost of his reputation. Before the monument was built, Colonel Buck’s reputation did not include vengeance seeking, mistresses or witch burning (not that witches were burned in New England). So, the story of how Jonathan Buck became cursed appears to have been concocted to explain the stain, not that the stain appeared to perpetuate his sins.

But the question remains – which came first, the cursing or the leg?

David Goudsward, raised on the summit of Scotland Hill, Haverhill, brings his New England sensibilities and respect for historical perspective his work. Although living in Florida, his bibliography consists primarily of New England topics. He recently compiled and edited, “Snowbound with Zombies,” a collection of supernatural stories inspired by Poet John Greenleaf Whittier. His latest book, “Horror Guide to Florida,” co-written with his brother Scott, is available via Amazon. (See Members Shop.) He is WHAV’s Open Mike Show’s historian.