Part 3 of an occasional series.

State officials report a housing shortage as demand far outstrips supply. In Haverhill, some residents wonder where they fall in the city’s priorities after development has increased in recent years. In light of a contentious zoning board meeting in January, a WHAV series explores concerns raised about impacts on the environment, overdevelopment with insufficient infrastructure and the character of long-settled neighborhoods changing.

“You have to know the Wood School neighborhood in order to understand why this is a concern,” Josiah Morrow said at a January zoning board meeting after he and other neighbors showed up to oppose a development. “This is an enclave in Bradford. It’s much different than other parts of the town. It is very quiet, secluded.”

Protecting the character of their over 100-year-old neighborhood was a common refrain among the dozens of residents who successfully reduced a proposal from four homes to three. Housing Advocate Kassie Infante, who is on the Board of Appeals, was one of a few members who voted for the developer’s request to override zoning law, which the board ultimately denied.

While she acknowledged that more construction would bring greater flooding, as WHAV reported in part one of this series, she said the dire need for housing means people, in Haverhill and across the state, must start letting developments through.

“It really hurts,” she said, when someone at the January meeting complained that the development would affect the view from their backyard, or when others said the area is unsuitable for children because of a lack of sidewalks.

“The underlying message, or at least how I interpret it, and how I know even my own family members do, is, families don’t belong in that neighborhood. You don’t belong,” she said. “And so [for] me, as someone who is probably going to have a family soon, as a person of color, it’s reminiscent of the type of exclusion that we’re supposed to be against.”

After graduating and first going into education, Infante said she became associate director for operations at Abundant Housing Massachusetts because of the issue’s significance to all aspects of a person’s life. Some people she’s close to struggle with housing access, too.

“I realized, so many of my own family members and kids in the education system were struggling with housing insecurity,” she said. “They were struggling through the pandemic to even be able to do their homework or focus because they’re living in an intergenerational home where there’s like 10 people for two or three bedrooms, and I saw this as a pattern. And I thought, ‘well, what’s more important than the roof over our head.’”

She said she didn’t know, “we are actually, today, in Massachusetts, we are more segregated, today, by race and class, than we were in the 1980s. That’s something I didn’t know until I started this job, and that really compelled me to do this work.”

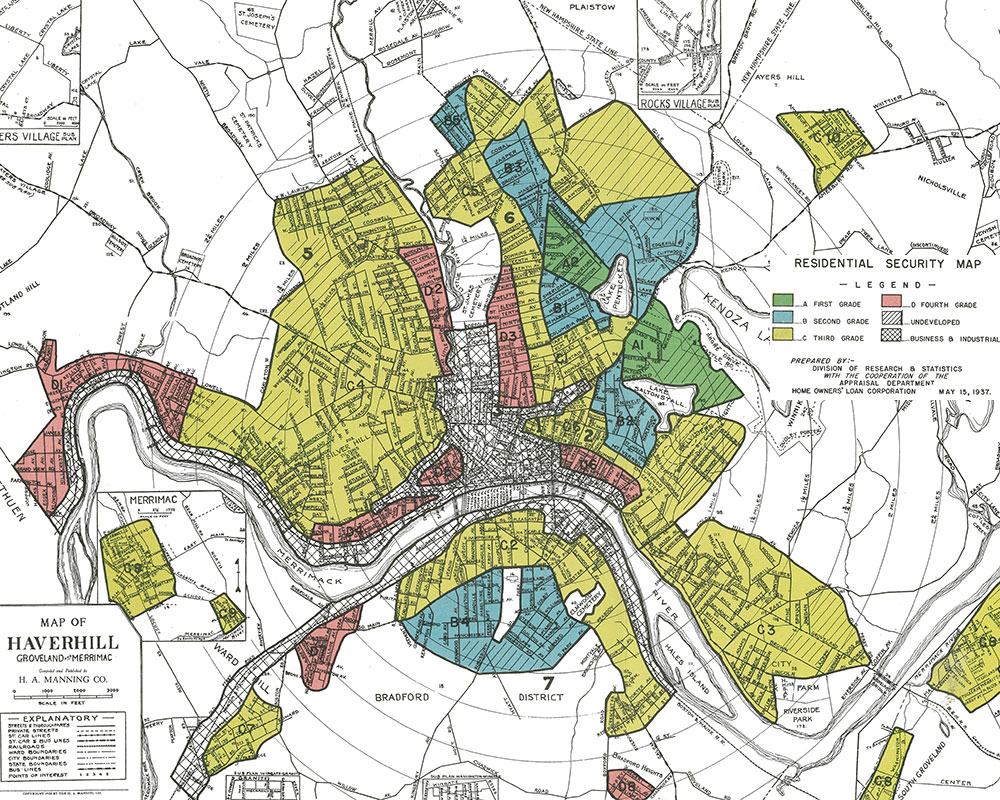

Redlining in Haverhill is still visible today, according to Infante. A now-illegal practice, the federal government in the early 1900s designated certain areas undesirable if immigrants or Black people lived there. In some cases, even one Black family was enough to prevent banks from offering mortgage loans to anyone in that neighborhood.

State Rep. Andy X. Vargas described the impact of the practice on Haverhill in a WBUR article, saying, “When you look at the redlining maps that were created in the early 1900s and you overlay that with the lowest-income census tracts of today, they almost identically match up. There are systemic forces at play from 100 years ago that are still affecting the socioeconomic status of families today.”

Federal maps from the 1930s deemed Vargas’ neighborhood, the Acre, hazardous. Today, Infante said a fear of change should not block developments that would help address the urgent, statewide housing shortage, not to mention historical inequities.

“I personally don’t feel like a personal righteousness and unwillingness to accept change, precedes people’s rights to be housed. I think we’re in an extreme housing shortage, and I know for a fact that, if those two duplexes were to be built, I just think about all the people that could have lived there,” she said, referring to the proposal Wood School residents opposed. “The opportunity to even live in something like a duplex is enormous.”

Duplexes are more affordable than single-family homes, according to Infante. Much of her work, she said, pushes for more “missing middle housing,” which includes anything between high-rise apartments and single-family homes–like duplexes and triplexes.

In Infante’s eyes, there’s a paradox at the center of the housing crisis. On the one hand, she said, is the necessity to build “deeply affordable housing” and, on the other, the American conception of homeownership, which defines a home as an appreciating asset and the key to building wealth.

“And I think that’s a part of why people show up to meetings so righteous,” she said. “They’re feeling like they’re protecting their property values.”