The City of Haverhill last Friday asked a federal court to dismiss a suit brought by former Patrolman and School Committee member Scott W. Wood Jr., saying Wood himself caused the release of the background checks that, he says, cost him two police jobs, and the truth would have been revealed regardless.

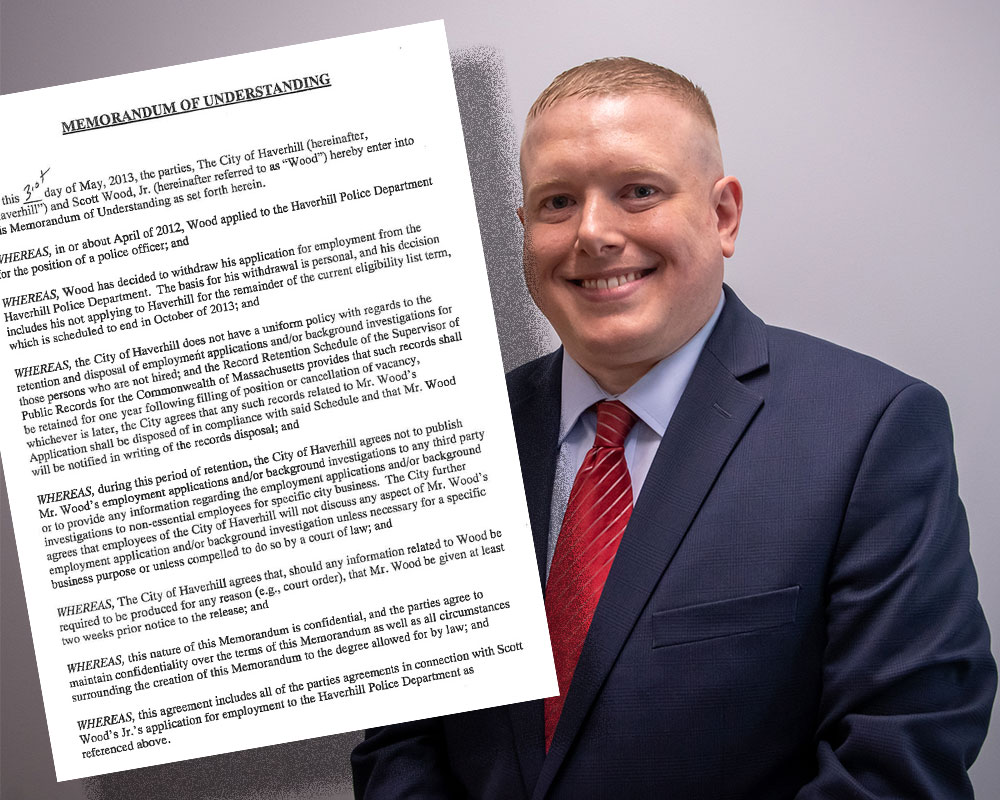

The motion to dismiss was filed on behalf of former interim Police Chief Anthony L. Haugh and current Police Chief Robert P. Pistone by the city’s outside law firm. Attorney Deborah I. Ecker of KP Law of Boston, took aim at Wood’s accusation the city violated its May 31, 2013 memorandum of understanding to eventually destroy a 2013 police background check.

“It was not the Haverhill defendants who unnecessarily, unreasonably or excessively published unidentified statements about the 2013 background investigation to which plaintiff (Wood) objects, but plaintiff when he filed his lawsuit and spoke to the press,” she wrote, referring to Wood’s original June lawsuit filed in state court and later withdrawn.

As WHAV reported first, Wood filed suit in U.S. District last October, claiming information from a resurfaced 2013 background check affected his employment at both Haverhill’s and Wenham’s police departments. The investigation and another one last year alleged Wood used racist and sexist language and made unwelcome sexual advances.

Ecker cited two paragraphs from the written 2013 agreement that explain the limits of the confidentiality it promised, applying only “to the degree allowed for by the law.” The city previously rejected WHAV’s public records request for the pact, but an unsigned copy was included with the city’s filing Friday.

In Wood’s suit, lawyer Sean R. Cronin of Boston described the matter as “unlawfully based employment decisions upon an unlawful, flawed, unreliable and unsubstantiated 2013 background report that the City of Haverhill agreed to destroy.”

Even if the document had been destroyed, Ecker wrote, officials including former Haugh and Pistone would still have been legally obligated to report information to the district attorney. U.S. Supreme Court decisions in Brady v. Maryland in 1963 and Giglio v. United States in 1972 suggest that state prosecutors keep such information to share with defense lawyers if necessary to judge the credibility of the police officer.

In addressing Wood’s allegations aside from breach of contract, she pointed out officials like Haugh and Pistone also have “conditional privilege,” a law that gives them immunity from being sued as long as they act legally and in good faith. The law aims to give officials some breathing room to make decisions and announcements in a timely manner.

She disputed Wood’s accusations of defamation—that the background report harmed his reputation—by pointing out that, by definition, defamatory statements must be false. Even if some information in the report is shown to be false, she continued, conditional privilege may still protect the chiefs.

She dismissed his claims of business interference, retaliation by the two communities after he hired lawyers, civil rights violations, loss of privacy and unlawful disclosure of electronic communications, citing a lack of malicious intent on the part of officials or coordination between Haverhill’s and Wenham’s police departments.

In addition, she called Wood’s wrongful termination claim into question, pointing out Wood did not attend a full-time police academy, “a prerequisite for plaintiff to work as a police officer in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, in any capacity, as a result of the so-called ‘Police Reform’ Act.”

As of news deadline, Wood had not yet filed a response to the city’s motion to dismiss.