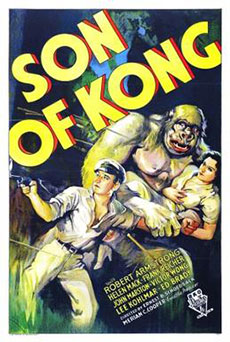

In 1933, nine months after the success of a little film called “King Kong,” RKO Pictures released “Son of Kong.” In the sequel, filmmaker Carl Denham is broke. Blamed for the destruction caused by Kong in New York, he hides in his boarding house. His landlady can barely keep the process servers outside and away from him. He leaves New York by freighter and ends up back on Skull Island.

The landlady was played by actress Kathrin Clare Ward, born in Bradford as Katie Clare O’Connor on Nov. 2, 1871, the fifth child of Irish immigrants James and Catherine (Welch) O’Connor, who worked in the shoe industry. As a child, she saw her older siblings leaving school to work. In the 1880 census, her 16, 14 and 12-year-old brother and sisters were already working in a hat shop.

As soon as she turned 21, Katie fled Haverhill to avoid the factory life of her family. She moved to Boston and used her remarkable voice and a memorized repertoire of Irish songs to make a living. There is no record of Katie ever returning to Haverhill. Her parents were dead by 1907, and with the low opinion of theater people in some circles, she would unlikely have been welcomed home.

By the late 1890s, she had moved to New York City with a thriving career in nightclubs and private events. As Katherine Klare, she parlayed that into a popular member of a musical comedy troupe. An interview at the beginning of the 1905 season noted that she had decided to join the vaudeville circuit in 1906. New York City was dismayed but not surprised. Vaudeville was the logical next step for a rising show business career. She quickly graduated to a headliner on the vaudeville circuits, singing Irish songs as Katherine Klare, the “Irish Thrush.” Several newspaper reviews considered “the new Maggie Cline,” Haverhill’s other successful Irish chanteuse. There’s no record of how Maggie Cline felt about the description, considering Cline didn’t retire until 1917.

In 1914, Katherine O’Connor married another singer on the circuit, Charles B. Ward, between performances in Chicago. She and Ward performed together intermittently as they toured with different companies. Ward not only wrote his own songs, he also owned New-York Music Company. This publishing house printed and distributed sheet music, his in particular. His most famous song was “The Band Played On,” which everyone knows by the opening lines. “Casey would waltz with a strawberry blonde.”

The Wards continued to tour but were starting to prefer West Coast circuits. The “Irish Thrush” expanded appearances to include light opera. The Wards were soon living in San Francisco, touring only locally. When Ward died in 1917, Katherine Clair Ward was ensconced in San Francisco society. She had a steady income thanks to the publishing company residuals, and she dabbled in local theater, but soon grew bored. Within a decade, she decided to move to Hollywood.

Ward probably didn’t move to Tinsel Town looking to be a movie star. It was the mid-1920s. Talking pictures were still experimental. Al Jolson’s “Jazz Singer,” the first feature-length motion picture with sound, would not appear until 1927. And, as a solidly built Irishwoman in her 50s, Ward knew she was no longer leading lady material.

Hollywood appealed to Ward because, after decades of touring the vaudeville and burlesque circuits, she knew everyone. All the actors and crew who saw vaudeville dying as films took over went to California to try their luck.

Movie poster for “Son of Kong.”

She didn’t need the money, but to break the tedium and see old friends, she became a “six-liner,” a bit player hired for one day stints and usually had less than six speaking lines. She launched a new career playing landladies, mothers-in-law and hired help. Having an Irish accent she could switch on and off helped. Most of the time, the roles were uncredited, which was the norm. Even her part in “Son of Kong,” which had more than six lines, was uncredited.

Kathrin Clare Ward was her stage name in the agency casting catalogs, but her few credited roles, so she may have used several versions before settling on her final choice. She appeared as Katherine Ward, Katherine Clair Ward, and Katherin Ward, as well as Kathrin Clare Ward. Kathrin Clare Ward was also the one on her obituary, so the other variations may have been studios not particularly concerned about the bit players.

She may not have cared. In 1929, now that there was sound, her late husband’s songs started appearing in movies. A percentage of each use came to her via the music company. Kathrin Clare Ward was never in danger of being a starving artist in Hollywood.

She died Oct. 14, 1938, in Los Angeles, Calif., having appeared in five films the year before. She was 67 and had been performing for 46 of those years. Her brief obituary in the Los Angeles Times notes her death “removed another veteran from theatrical ranks.”

During her film career, she appeared as an extra in films starring fellow ex-vaudevillians like Will Rogers, Mae West, Joe E. Brown, and Olsen & Johnson. She worked with directors such as Busby Berkeley, Cecil B. DeMille, Mack Sennett, and D. W. Griffith.

David Goudsward, raised on the summit of Scotland Hill, Haverhill, brings his New England sensibilities and respect for historical perspective his work. Although living in Florida, his bibliography consists primarily of New England topics. He just released his 22nd book, a revised and expanded edition of his award-winning “Ancient Stone Sites of New England.” The latest and all of Goudsward’s earlier titles may be ordered from local bookstores or from Amazon.