Hear Whittier’s Last Poem read aloud

There is something poignant about “last” things. The word last often possesses the sad, sometimes heroic, connotation of finality, including death. Think of a loved one’s last words, or the last time you saw a good friend, or a soldier’s last stand. Whittier’s last poem holds this poignancy. It is also, as I will show later, a key to understanding the poet’s deepest feelings and thoughts upon his approaching death, and a testament of his writing genius.

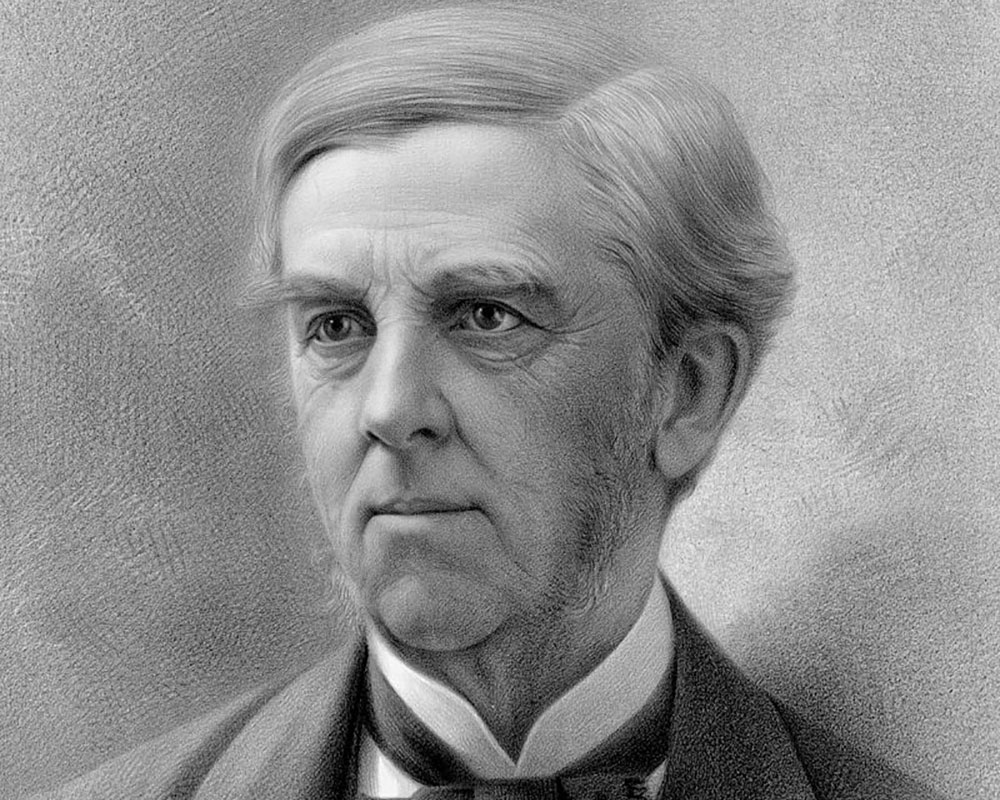

When John Greenleaf Whittier wrote “To Oliver Wendell Holmes,” his last poem, in July, 1892, it was to celebrate Holmes’s upcoming 83rd birthday on August 29. But it was a special poem for Whittier also, then 84, because by this time the Haverhill-born poet, abolitionist, and supporter of women’s emancipation and workers’ rights, knew that death was imminent. He was having trouble hearing and his eyesight was fading, and he often lacked his customary enthusiasm for receiving admirers from the United States and abroad who wanted to visit him in his Amesbury home. Although he still followed local and national news, supported causes, and wrote poems, he did so at a greatly diminished pace (Woodwell 516-525).

John Greenleaf Whittier.

In fact, the appearance of the poem in the September, 1892 issue of The Atlantic Monthly coincided with Whittier’s death, which took place on September 7 during a visit with friends in Hampton Falls, New Hampshire. He passed away quietly in bed. During his final days he would often repeat, “I love all the world,” as if to reinforce the major impetus of his life (Woodwell 527). His death was a national story, and many mourned (Woodwell 527-533).

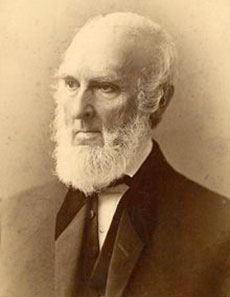

His friendship with Cambridge-born Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., a physician, social commentator, and poet (author of “Old Ironsides,” “The Last Leaf,” “The Chambered Nautilus”), began in late 1853 when Holmes visited Haverhill to lecture at the Haverhill Lyceum (Pickard 2: 247). Whittier took an immediate liking to him, writing to James Fields on January 1, 1854: “I met Holmes for the first time the other night. – There is a rare humor in him, and I suspect that he knows it. But I like him” (Pickard 2: 247). This short encounter was the beginning of a lifetime friendship that included a sincere appreciation of each other’s works. They, along with their other literary friends, including William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878), Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882), Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), and James Russell Lowell (1819-1891), were considered at the apex of the literary pyramid in Massachusetts and the country.

By the summer of 1892, however, Holmes was nearly 83 years old, and Whittier was 84, and they had come to regard themselves not only as friends but as survivors. When their friend, James Russell Lowell, died on August 12, 1891, Whittier wrote to Holmes six days later: “…we are now standing alone. The bright beautiful ones who began life with us have all passed into the great shadow of silence… I am wondering what our beloved Lowell is thinking and doing in the life beyond us. Has he found Emerson and Longfellow?” (Pickard 3: 586-587) Holmes wrote back a short time later asking for permission to meet with Whittier at the latter’s retreat at Oak Knoll, in Danvers, stating in his customary lightness, “We…are no longer on a raft, but we are on a spar” (Pickard 3: 587). The two friends did meet on September 1, where they had “a pleasant hour of talk…saddened by memories of the friends who had left them so much alone but only a little; old men have become used to losses” (Woodwell 518).

So, what is the poem, “To Oliver Wendell Holmes,” about? It is a celebratory birthday poem from one surviving friend to another, and it is also a poem of praise (a panegyric) of Holmes, the man and the poet. In addition, it may be viewed as Whittier’s own last testament, expressing his deepest and most abiding values upon his approaching death. Reading it is well worth the effort in the enjoyment and lessons it can give.

I would recommend reading the poem aloud a number of times to appreciate its natural cadence and harmony. This is an important first step because naturalness is a major hallmark of Whittier’s aesthetic, and it is especially apparent in this poem because, by this time, Whittier had thoroughly mastered his craft. Note that part of the pleasure you feel from reading it comes from the alternation of 10-syllable and 6-syllable lines. The poem follows:

To Oliver Wendell Holmes

Among the thousands who with hail and cheer

Will welcome thy new year,

How few of all have passed, as thou and I,

So many milestones by!We have grown old together; we have seen,

Our youth and age between,

Two generations leaves us, and to-day

We with the third hold way,Loving and loved. If thought must backward run

To those who, one by one,

In the great silence and the dark beyond

Vanished with farewells fond,Unseen, not lost; our grateful memories still

Their vacant places fill,

And with the full-voiced greeting of new friends

A tenderer whisper blends.Linked close in a pathetic brotherhood

Of mingled ill and good,

Of joy and grief, of grandeur and of shame,

For pity more than blame, –The gift is thine the weary world to make

More cheerful for thy sake,

Soothing with Miserere pains,

With the old Hellenic strains,Lighting the sullen face of discontent

With smiles for blessings sent.

Enough of selfish wailing has been had,

Thank God! for notes more glad.Life is indeed no holiday; therein

Are want, and woe, and sin,

Death and its nameless fears, and over all

Our pitying tears must fall.Sorrow is real; but the counterfeit

Which folly brings to it,

We need thy wit and wisdom to resist,

O rarest Optimist!Thy hand, old friend! the service of our days,

In differing moods and ways,

May prove to those who follow in our train

Not valueless nor vain.Far off, and faint as echoes of a dream,

The songs of boyhood seem,

Yet in our autumn boughs, unflown with spring,

The evening thrushes sing.The hour draws near, howe’er delayed and late,

When at the Eternal Gate

We leave the words and works we call our own,

And lift void hands aloneFor love to fill. Our nakedness of soul

Brings to that Gate no toll;

Giftless we come to Him, who all things gives,

And live because He lives.

Now take a look at its major parts. In the first four stanzas old age is the theme as Whittier reminds Holmes that they are both getting old and still remember fondly old friends who have passed away. He mentions that both he and Holmes have been loving to and loved by others. (We have already seen that love is a major impetus in Whittier’s life.) Next, appreciate stanzas 5-10, where you see Whittier’s depiction of the world as a pretty dreary place, and of Holmes’s wit, wisdom, and optimism helping to make it a more cheerful place. Finally, see in the last three stanzas how he returns to the theme of old age, recalling their life span from “songs of boyhood” to “evening thrushes,” and anticipating the gift of love and eternal life that they can look forward to. This is the faithful Quaker returning to his God.

Works Cited

Pickard, John B. The Letters of John Greenleaf Whittier. 3 vols. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1975.

Woodwell, Roland H. John Greenleaf Whittier: A Biography. Haverhill: Trustees of the Whittier Homestead, 1985.