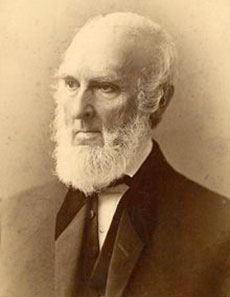

John Greenleaf Whittier.

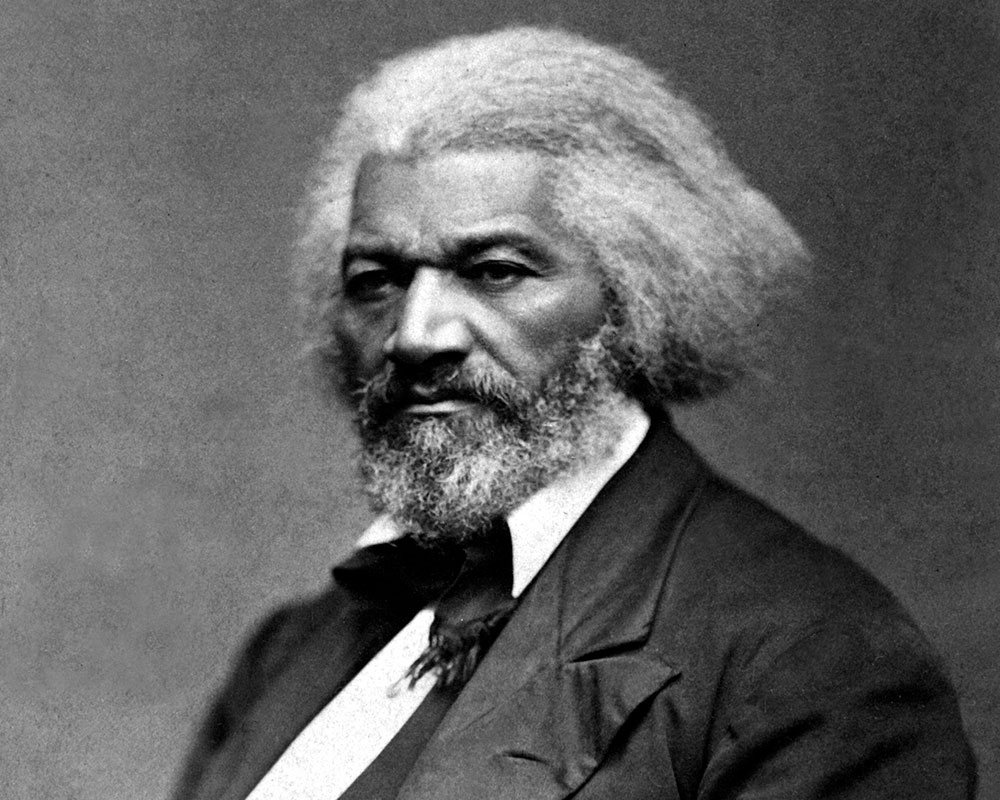

“Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself (full title),” published in 1845, is a graphic memoir depicting the cruelty of slavery as it existed in the South during the early 19th century. The account was all the more compelling because Douglass was a recent run-away slave who witnessed first-hand the actions he described. The slim volume was an immediate success, and it has become, deservedly, a classic on reading lists in schools and colleges today. I think that every American who wants to understand the ravages of slavery would be well advised to read it.

There are only five poems mentioned in the memoir, two of which are Whittier’s (the others by Cowper, Shakespeare, and Douglass himself). The first that appears is an excerpt from the poem, “The Farewell of a Virginia Slave Mother to Her Daughter, Sold into Southern Bondage” (1838). It is included in a moving segment that deals with the dismal treatment of Douglass’s grandmother. Following is the complete piece:

…If anything in my experience, more than any other, served to deepen my conviction of the infernal character of slavery, and to fill me with unutterable loathing of slaveholders, it was their base ingratitude to my

poor grandmother. She had served my old master faithfully from youth to

old age. She had been the source of all his wealth; she had peopled his

plantation with slaves; she had become a great grandmother in his service.

She had rocked him in infancy, attended him in childhood, served him

through life, and at his death wiped from his icy brow the cold death-sweat,

and closed his eyes forever. She was nevertheless left a slave—a slave for

life—a slave in the hands of strangers; and in their hands she saw her

children, and her great-grandchildren, divided, like so many sheep, without

being gratified with the small privilege of a single word, as to their or her

own destiny. And, to cap the climax of their base ingratitude and fiendish

barbarity, my grandmother, who was now very old, having outlived her old

master and all his children, having seen the beginning and the end of all of

them, and her present owners finding she was of but little value, her frame

already racked by the pains of old age and complete helplessness fast

stealing over her once active limbs, they took her to the woods, built her a

little hut, put up a little mud-chimney, and then made her welcome to the privilege of supporting herself there in perfect loneliness; thus virtually

turning her out to die! If my poor old grandmother now lives, she lives to

suffer in utter loneliness; she lives to remember and mourn the loss of

children, the loss of grandchildren, and the loss of great-grandchildren.

They are, in the language of the slave’s poet, Whittier, –Gone, gone, sold and gone

To the rice swamp dank and lone,

Where the slave-whip ceaselessly swings,

Where the noisome insect stings,

Where the fever-demon strews

Poison with the falling dews,

Where the sickly sunbeams glare

Through the hot and misty air;–Gone, gone, sold and gone

To the rice swamp dank and lone,

From Virginia hills and waters–

Woe is me, my stolen daughters!The hearth is desolate. The children, the unconscious children, who

once sang in her presence, are gone. She gropes her way in the darkness of

age, for a drink of water. Instead of the voices of her children, she hears by

day the moans of the dove, and by night the screams of the hideous owl.

All is gloom. The grave is at the door, and now, when weighed down by the

pains and aches of old age, when the head inclines to the feet, when the

beginning and ending of human existence meet, and helpless infancy and

painful old age combine together—at this time, this most needful time, the

time for the exercise of that tenderness and affection which children can

only exercise toward a declining parent—my poor old grandmother, the

devoted mother of twelve children, is left all alone, in yonder little hut,

before a few dim embers. She stands—she sits—she staggers–she falls—

she groans—she dies, and there none of her children or grandchildren

present, to wipe from her wrinkled brow the cold sweat of death, or to place

beneath the sod her fallen remains. Will not a righteous God visit for these

things?” (Douglass 37-38)

Few would not be moved by the cadence and emotion–the poetry–in both pieces, one in prose, the other in verse. The fact that Douglass refers to Whittier as “the slave’s poet” underlines Whittier’s popularity in 1845 as an abolitionist, to the point of having his poems become known and appreciated by slaves themselves.

The second excerpt, which is a critique of hypocritical Christians who justify the institution of slavery, the same critique that Douglass makes, is from the poem, “Clerical Oppressors” (1836):

Just God! And these are they,

Who minister at thine altar, God of right!

Men who with their hands, in prayer and blessing, lay

On Israel’s ark of light.What! preach and kidnap men?

Give thanks, and rob thy own afflicted poor?

Talk of thy glorious liberty, and then

Bolt hard the captive’s door?What! servants of thy own

Merciful Son, who came to seek and save

The homeless and the outcast, fettering down

The tasked and plundered slave!Pilate and Herod friends!

Chief priests and rulers, as of old, combine!

Just God and holy! Is that church which lends

Strength to the spoiler thine? (Douglass 76)

After the publication of his book, Douglass took a 19-month journey to England and Ireland to escape from persecution by those he named and offended in his narrative. While in Ireland he re-worked and re-published his work (September 1845), paying Whittier an even greater compliment by placing the following additional excerpt from his indignant poem, “Expostulation,” (1834) on the title page itself:

What, ho! our countrymen in chains!

The whip on woman’s shrinking flesh!

Our soil yet reddening with stains

Caught from her scourging, warm and fresh!

What! mothers from their children riven!

What! God’s own image bought and sold!

Americans to market driven,

And bartered as the brute for gold!

Ironically, on June 15, 2020 Whittier’s statue in Whittier, California, a city named after him, was defaced with the words “BLM” and “(expletive) Slave Owners,” and spray-painted. Four days later, his statue in Amesbury, Massachusetts, location of the Whittier Home, was also spray-painted. These occurred in the aftermath of the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020.

Work Cited

Frederick Douglass, Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself. Ed. William L. Andrews and William S. McFeely. New York: Norton, 1997.