Harmony Montgomery. (Courtesy of the Office of the Child Advocate.)

The state Department of Children and Families, a Massachusetts court and several lawyers are being blamed for failing seven-year-old Harmony Montgomery before her disappearance.

The little girl was first placed in foster care during August 2014 after the Haverhill office of the Department of Children and Families investigated three separate reports alleging “neglect.” She was born two months earlier to Crystal Sorey and Adam Montgomery, but was in Sorey’s care since Montgomery was in prison, charged in connection with shooting a man in the face Jan. 24, 2014 during a drug deal turned robbery in Haverhill.

State investigators said Soreys “parental substance use” led to her placement in foster care.

The report said state officials undervalued Harmony’s needs during custody discussions and insufficiently examined whether her father was prepared for caretaking. Assigning blame across virtually every step in the process, the Office of the Child Advocate said those responsible for ensuring Montgomery’s safety and care made “a series of decisions that did not place her at the center,” misjudging the risks that she would face and putting too much emphasis on her parents’ rights.

The 101-page report detailing its findings about how DCF, the Committee for Public Counsel Services and the Juvenile Court handled Montgomery’s case in the first four and a half years of her life, up until a judge in February 2019 awarded custody across state lines to her father. The conclusions drew criticism from CPCS, which argued that the report “disregards the constitutional rights of children and parents and the responsibilities of attorneys for children and parents.”

Montgomery has been missing since November 2019, less than a year after she moved to New Hampshire to live with her father, whom Granite State police arrested in January in connection with Harmony’s disappearance.

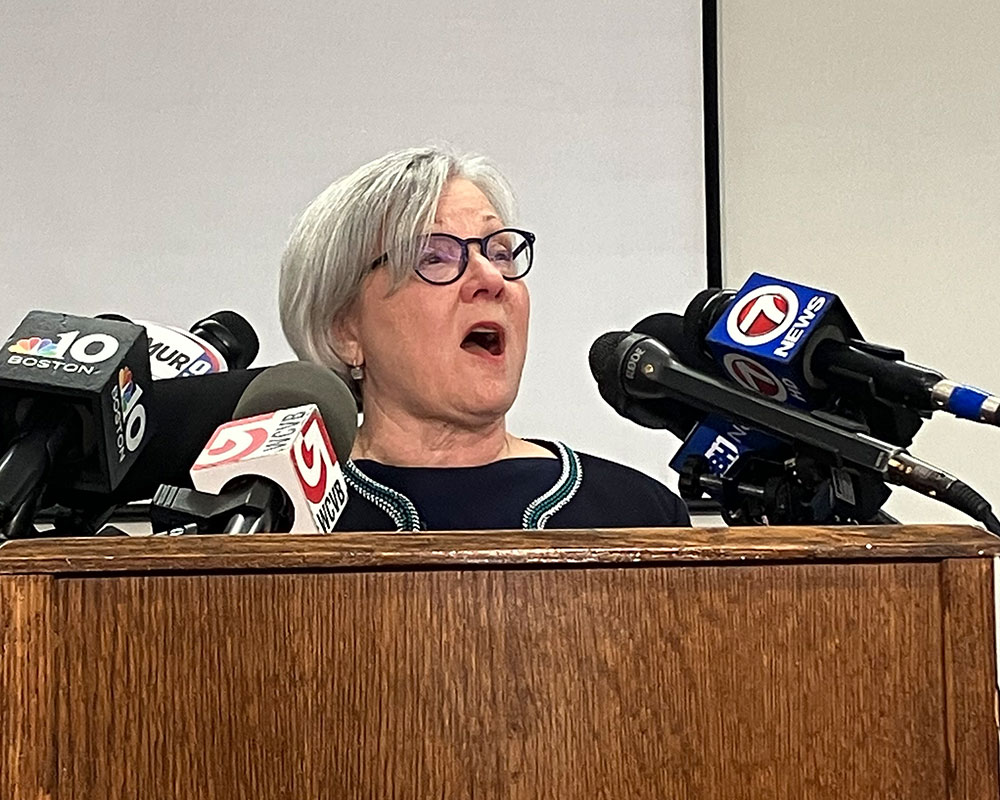

OCA Director Maria Mossaides said “We do not know Harmony Montgomery’s ultimate fate, and unfortunately, we may never, but we do know that this beautiful young child experienced many tragedies in her short life and that by not putting her and her needs first, our system ultimately failed her.”

In the early years of her life, Harmony, who has visual disabilities, bounced between foster care and two separate reunifications with Sorey. Her father had stretches of contact interspersed with long periods featuring no communication, according to OCA.

The investigative team said DCF in that span focused its attention on Sorey and not on Montgomery, who at first was in prison and was later released. While the department facilitated supervised visits between Adam and Harmony, DCF never held him accountable for completing tasks on his action plan nor completed an assessment, according to the report.

Mossaides said that inaction left officials with “little understanding of his family or personal history from which to develop an action plan and from which they could assess his capacity to parent Harmony.”

By late 2018, Adam Montgomery was in regular contact with DCF at the same time that Sorey was “unstable in her sobriety,” and the father sought to have Harmony placed into his custody in New Hampshire.

OCA described substantial breakdowns in a judge’s February 2019 decision to award custody to Adam Montgomery. During the court proceedings, Mossaides said, a DCF lawyer objected to the move, but did not offer a strong legal argument. Harmony Montgomery’s attorney—whom the OCA did not name but described as publicly appointed by CPCS—did not submit evidence about the girl’s needs, her desired legal outcome or what she would need “to be safe and to thrive,” Mossaides said. OCA did not identify the judge involved in the case, but the Boston Globe reported it was now-retired Judge Mark Newman.

The report made extensive recommendations for overhauling work done by DCF, the courts and CPCS to address what the Child Advocate deemed to be significant gaps contributing to the Harmony Montgomery case.

OCA called on DCF to develop a comprehensive plan to sufficiently assess both parents, which Mossaides said aims to ensure “fathers are provided the same level of attention as mothers,” and for state officials to increase training about applying the interstate compact. The office also called for convening a working group to weigh broader policy shifts to balance the best interests of children with parents’ rights.

A spokesperson for DCF said the department “remains committed to engaging with the court to increase timely permanence for children and to assure safety and for the child’s best interest to remain paramount.”

“The Office of the Child Advocate report illustrates the grave responsibility of balancing the child’s safety and best interest and a parents’ legal rights to have custody of their child,” spokesperson Andrea Grossman said in a statement. “The Baker-Polito Administration agrees with the OCA that the safety of the kids in DCF care, and servicing their needs, should be the priority not only of DCF but of all the participants in our child protection system. As the OCA report states, the Department continues to make meaningful and lasting reforms to address these complex issues when a case comes before the court.”

Investigators took specific aim at CPCS, which Mossaides said trained and certified the attorneys that represented Harmony Montgomery, Adam Montgomery and Sorey. The group’s policies, she said, “should be revised to ensure the best interests of children are presented to the court in addition to the direct advocacy to support the child’s best wishes.”

“One of our concerns is that children’s attorneys do not appear to take a robust role in presenting the needs of the child and that they are more likely to defer to what advocacy of the parents’ attorneys (says) rather than providing independent advocacy, which is why we hope the Committee for Public Counsel Services will take a hard look at their current standards,” Mossaides said.

While CPCS said it agreed with some of the recommendations, the organization blasted OCA’s report as a whole, alleging that it “disregards the constitutional rights of children and parents” and also misconstrues the interstate compact.

“Whenever the state intervenes in a family’s life, the goal should be keeping children safe and in a permanent home where their overall wellbeing is being promoted,” CPCS Chief Counsel Anthony Benedetti said in a lengthy statement. “One critically important way to do that is to honor the rights of parents and children, including their constitutional right to be heard. That is what we do every day. We have an extensive training program through which we have taught generations of attorneys how to practice this area of law. We oversee hundreds of attorneys across the state to ensure that the quality of representation meets our standards. We are always examining ways to improve what we do as part of this vital work.”

Benedetti said CPCS submitted 16 pages of feedback to a draft version of the OCA report in March but that “very few of our suggestions” featured in the office’s final recommendations.

“Too often it is the case that sad facts result in bad law, and that will be the situation here if the OCA recommendations are adopted,” Benedetti said. “This report calls for fundamental changes to the legal system in a way that fails to consider the constitutional rights of our clients, our responsibilities and obligations as attorneys and the existing law. These changes would pay a disservice to Miss Montgomery, and the thousands of children who are entitled to an attorney during the hardest moments of their childhood.”

Gov. Charlie Baker proposed requiring the state to appoint a guardian ad litem—which OCA described as a “neutral professional who participates in court proceedings on behalf of a child”—in every Juvenile Court proceeding involving a child who has allegedly been subject to abuse and neglect.

He included that language, plus $50 million to fund the recruitment, training and salaries of guardians ad litem, in a mid-year budget bill, but lawmakers omitted those reforms from the version they approved that ultimately earned Baker’s signature.

Mossaides said she agrees with Baker’s proposal to expand the role of guardians ad litem “in order to do the investigation, to ensure that the placement is a safe place for a child to be returned to.”

The Montgomery report landed more than a year after OCA published the results of a similarly detailed investigation into the death of David Almond, a Fall River teenager with autism.

Mossaides said the decisions to place Montgomery and Almond with their fathers both happened in 2019, and she added that many of her office’s 26 recommendations in the Almond case could be applied to the Montgomery case.

Since the Almond report in 2021—which Baker at the time called “incredibly damning”—DCF and the Juvenile Court have made “extensive improvements,” Mossaides said Wednesday. Her office made a similar conclusion in a March report to lawmakers.

According to the administration, reforms already implemented or underway include a new dedicated policy for working with parents and children who have disabilities and a multi-level review policy when a child is within 120 days of being reunited with a parent.

The state is also working with five New England neighbors on developing better communication and cooperation for placing children across state lines.