Almost 300 years ago today—give or take a few days for calendar adjustments over the centuries—Haverhill suffered one of its most calamitous natural spectacles.

By most accounts, the summer of 1727 had been unpleasant in the Merrimack Valley. It had been excessively hot, punctuated by heavy rainstorms with strong winds, frequently accompanied by thunder and lightning. As summer turned to autumn, it was assumed things would cool down to more bearable levels.

Instead, on Sept. 16, “a mighty tempest of wind and rain” slammed into the region. Trees were uprooted across the area, and a tidal surge swept 200 loads of drying hay from the Newbury salt marshes. Based on damage and wind directions reported in Boston, the North Shore was hit by the powerful right-front quadrant of a category one hurricane that came ashore on the South Shore.

The beleaguered colonists were forced to salvage their harvest, repair damage and clean up storm debris before winter arrived. By the end of October, things were returning to normal.

Then, at 10:30 p.m., on Sunday, Oct. 29, 1727, the wrath of God was unleashed on the Merrimack Valley for three endless minutes. An earthquake, estimated to be at least 6.3 on the modern Richter scale, struck. It was centered off the coast of Newburyport. The aftershocks lasted for a week, shaking houses and filling the air with thunder. On the night of Dec. 24, two significant aftershocks produced loud thunder and jarred the houses again. This shock was reported from Charles River to Casco Bay.

This was not the first earthquake to strike the area, nor was it the last, but it may have been the most violent to hit the area. Seismic activity was terrorizing the Haverhill colony as early as 1643, with major quakes in 1755 and 1827. To this day, New England remains extremely seismically active, although most of the activity is measurable only by a seismograph. The area north of Boston is riddled with fault lines. The fault nearest to Haverhill is known as the Newbury-Clinton Fault Zone. Branching out from this main fault are hundreds of minor faults, spreading out like tendrils.

The Newbury-Clinton fault zone is not considered active. It is the geologic equivalent of a scar from the tortured past of the planet. It has probably not moved in more than 140 million years. However, when the active fault off the coast beneath the Atlantic Ocean moves, the energy travels along the old fault line as well, vibrating along its length like a plucked guitar string.

Foot wide fissures shattered the ground in Newburyport. In Newbury, more than 10 sand geysers erupted from the clay lowlands. When the sand was cast on fire, it burned like brimstone. Across the region, cellar walls collapsed, wells went dry and springs were redirected. Piles of sand appeared in the Merrimack River.

Hampton seemed to be nearest to the epicenter. Flashes of earthquake light were reported. One or two witnesses saw streams of bluish light running along the earth (piezoelectric discharge). South of town, the ground broke open and cast up water and fine bluish sand, liquefying the surrounding land.

Haverhill reported stopped clocks, collapsed chimneys, shattered brick houses and stone walls scattered in all directions. The aftershocks reverberated for the better part of the year, with 30 recorded between January and May of 1728.

Even Cotton Mather, New England’s most famous natural philosopher, didn’t know what to make of this earthquake. Its scope and power were far beyond the tremors occasionally reported. Mather wrote that the cause may also have natural causes, but this terrifying event merited serious theological reflection for now.

Ministers in the quake zone had no time or inclination for discussions of scientific or divine causes. They had more pressing concerns¬–terrified parishioners wanting to know why God shook the earth. The simple answer was the very tenet of Puritan mentality: New England was a land of sin, and God always punished sin. The Puritan mindset reasoned that New England was especially prone to divine retribution because, but being inhabited by Puritans, it was a divinely appointed place and held to a higher standard of behavior.

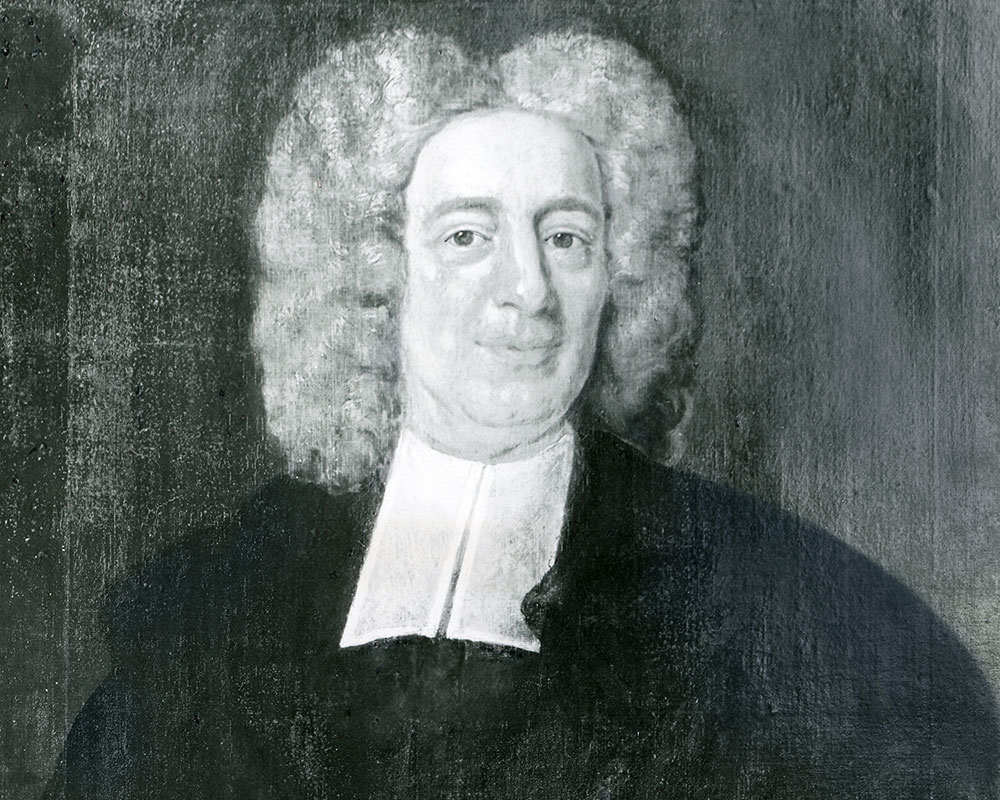

The earthquake rattled the religiously complacent, and repentance and reformation suddenly seemed prudent to even the congregation’s most lax members. John Brown, the minister of Haverhill’s First Parish, wrote to John Cotton, the Newton minister. Although the earthquake had been felt throughout Massachusetts, it was apparent the lower Merrimack Valley had felt the brunt of the seismic activity. Brown writes on Nov. 20, 1727, that not one day had passed without earthquake noise. He reports a sudden, if not unexpected, interest of the townsfolk in their immortal souls. Monday, Oct. 30, the day after the quake, Haverhill held a day of fasting with a full meeting house. With aftershocks still rocking the region, another day of fasting (again with a full meeting house) was held Nov. 1. Brown crossed over to Bradford on Thursday to help out the overwhelmed clergy in that village.

The governor declared Nov. 9 to be a day of thanksgiving. Fasting, prayer, special sermons—all to exalt the Lord, celebrate there had been no deaths and, hopefully, continue the robust church attendance. Brown admitted to Cotton that he barely had time to eat, let alone write a Thanksgiving sermon. He was too busy offering solace to the scared, advice to the devout, and support to the church’s formerly lapsed members. For a full week before and after the day of thanksgiving, he was tending his flock, morning until after sunset.

The result was what Brown felt was a general reformation. More than 200 Haverhillites were admitted to full communion in the year following the earthquake. Another 148 owned the covenant. Baptisms increased dramatically, as did those receiving the sacrament. It was not just Haverhill seeing this resurgence in seismically-induced religiosity. Brown reports tiny Exeter had 40 baptisms, and Amesbury couldn’t get people to stop praying and leave the meeting house.

In the aftermath of the Day of Thanksgiving, the special sermons were printed by the various ministers into pamphlets, available for a small fee to congregants and interested parties. Published sermons were a rare occurrence. Paper was scarce, and the sermons’ proliferation is evidence of the significance placed on the aftermath of the earthquake.

John Cotton’s pamphlet, “A holy fear of God, and his judgments, exhorted to: in a sermon preach’d at Newton, November 3. 1727. On a day of fasting and prayer, occasion’d by the terrible earthquake that shook New-England, on the Lords-Day night before,” included a copy of John Brown’s report from Haverhill, giving a rare firsthand account from the epicenter.

Cotton Mather was correct in pronouncing the Great Earthquake merited serious theological reflection. Still, numerous days of fasting and thanksgiving for a miraculous deliverance did not eliminate the aftershocks. So, in the long term, the earthquake added to a developing schism between Puritan theology and the burgeoning school of scientific rationalism, one that continues to reverberate to this day.

David Goudsward, raised on the summit of Scotland Hill, Haverhill, brings his New England sensibilities and respect for historical perspective his work. Although living in Florida, his bibliography consists primarily of New England topics. His latest book, “Sun, Sand, and Sea Serpents.” The book, his 17th published title, covers sea serpent reports from Florida, the lower eastern seaboard, and the Caribbean. “Sun, Sand, and Sea Serpents,” as well as Goudsward’s earlier titles, may be ordered from local bookstores or on Amazon.