On Oct. 18, 1927, Whittier Birthplace received a visitor. This, by itself, was not a particularly momentous event—the Birthplace had been open to the public since 1893 after former Haverhill Mayor James H. Carleton purchased the house and land and presented it to the Haverhill Whittier Club. This visitor was different, for he was as much a household name as Whittier himself—automobile magnate Henry Ford.

In 1927, Henry Ford had been active in historic preservation for over a decade, and was amassing a large collection of Americana. So large was his collection that he had been considering the creation of a museum to house and eventually display the items. But Ford was not interested in a static building of displays. He wanted a living museum, where salvaged buildings could still be used and artifacts could be placed in proper context. He already had a good idea how to approach the museum—he already had one.

In 1923, Ford had been approached to request funds to save the Wayside Inn in Sudbury, the inn that immortalized by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his Tales of a Wayside Inn. Instead of a contribution to the cause, Ford purchased the inn.

Ford’s previous preservation work made him aware of preservationist William Sumner Appleton Jr. (1874–1947), the founder of the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities (SPNEA, now Historic New England). Appleton’s criteria for preserving buildings ensured public support. SPNEA would purchase buildings which were not only historically significant but also architecturally attractive. His restorations were radical for the time, involving experts to assess what actually needed to be changed and how to approach the work, and then documenting those changes so that they could be reversed in the future.

The Whittier Birthplace fireplace, top, may have served as a template for the restoration of the Henry Ford-owned Wayside Inn’s fireplace.

With a historic building considered a significant literary landmark, Ford approached the repairs the same way he approached manufacturing—he wanted the best. So, he hired William W. Taylor away from Appleton and SPNEA. Taylor would be Ford’s local eyes build the collection and oversee the Wayside’s restoration. Then to insure the pastoral setting of the Inn, he bought 3,000 acres surrounding the structure. On this land, under Taylor’s advice, Ford began adding historic buildings such the one-room schoolhouse from Sterling that Ford believed was the actual schoolhouse in Sarah Josepha Hale’s poem “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Evolving his vision as he progressed, Ford also built a fully working grist mill and a church to make the property more like a village.

By 1926, Ford spent $2 million on the Wayside Inn ($27 million in current funds) but was looking to expand the concept closer to his base of operations in Michigan.

When Henry Ford visited the Whittier Birthplace in 1927, he was accompanied by Taylor and several friends. They had driven up from the Inn in Sudbury on a two-part mission. Taylor was examining first period buildings (1626-1725) in order to restore the Wayside Inn’s fireplace, stopping at both the Birthplace (built in 1688) and Duston Garrison (1697) to examine fireplace features as possible design templates for restorations at the Inn (1686). And Ford was there to examine a possible acquisition, which he chose not to share with newspaper reports of his visit, lest his interest start a bidding war. This acquisition would become one of the earliest pieces bought specifically for Greenfield Village, his planned living museum in Michigan. Henry Ford wanted Haverhill’s Rocks Village bridge toll house.

Built in 1828, the toll house is a 10-foot by 12-foot one-room, clapboard building, with a soapstone stove and windows on all four walls. It was designed to allow a toll keeper to stay out of the weather and provide enough room to continue working as a shoemaker in-between taking tolls and raising the drawbridge. Tolls were collected until 1868 when Essex County declared all highways to be free for public use, effectively assumed authority over the bridge, but not maintenance. The toll house remained in use for the drawbridge until 1912, when after years of minimal funding for repairs from Haverhill, West Newbury and Amesbury, the bridge was in such poor shape that it needed to be replaced.

A good Yankee never wastes anything, and James Colby was no exception. A former toll keeper, he purchased the empty building and had it hauled up the road to his yard on River Road to be a fulltime shoe shop until His death in 1920. His son Harry inherited the property and also used it briefly as a shoe shop until the factories downtown made such small operations obsolete. He became a foreman at a shoe factory and the toll house became a tool shed. By the time Ford and Taylor saw the structure, it was a battered relic. But the history of transportation included these little toll houses, a Ford collection primary focus, so Thomas was authorized to make arrangements to acquire it.

In April of 1928, the purchase was finalized and arrangements for transportation were in place. Thomas and a team of work descended on River Road. Based on the amount of damage, Thomas decided it was easier to gut the structure and restore it in Deerfield. Today, the toll booth once again stands guard at the foot of another bridge, the Ackley Covered Bridge, acquired in Pennsylvania. A coat of paint, an oil lamp and a toll price highlight the outside. The inside is remains a functional shoe shop; Ford had a cobbler in the shop making shoes as part of the living museum exhibits for a number of years. The biggest changes are a cast iron stove replacing the original soapstone, a chimney with half the height that it had in Haverhill, and the name. The Rocks Village Toll House is now known as “The Whittier Tollhouse & Shoeshop,” renamed because it was mentioned by Whittier in his Rocks Village poem “The Countess:”

Along the gray abutment’s wall

The idle shad-net dries;

The toll-man in his cobbler’s stall

Sits smoking with closed eyes.

You hear the pier’s low undertone

Of waves that chafe and gnaw;

You start,–a skipper’s horn is blown

To raise the creaking draw.

David Goudsward, raised on the summit of Scotland Hill, Haverhill, brings his New England sensibilities and respect for historical perspective his work. Although living in Florida, his bibliography consists primarily of New England topics.

More Photographs

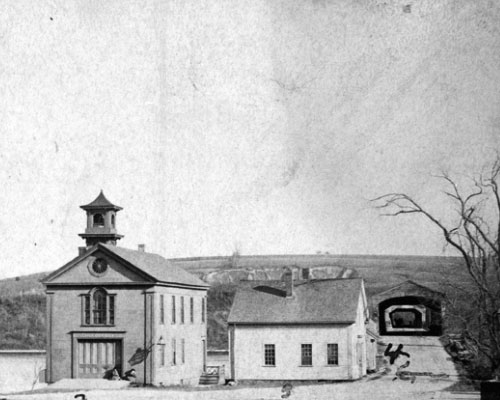

The Rocks Village Toll House in its original location (barely seen and identified by the handwritten number 4) at the entrance to the covered bridge. In the foreground are the Rocks Village Fire Station and a building described as a store or shop. (From the Collections of The Henry Ford.)

Great story. Imagine Henry Ford coming here to buy a shed. Lol

So exciting to read your article about Rock’s Village. Historic New England (www.historicnewengland.org) is working with the Rock’s Village Memorial Association (www.rocksvillage.org) to develop a walking tour about this fascinating neighborhood that will feature stories spanning the centuries and the people who lived and worked there. People such as the Chases who lost five of their nine children within two months to throat distemper; to Prince Davis born into slavery becoming a free head of household; to laborers becoming successful land owners and humble shoemakers turned downtown factory owners.