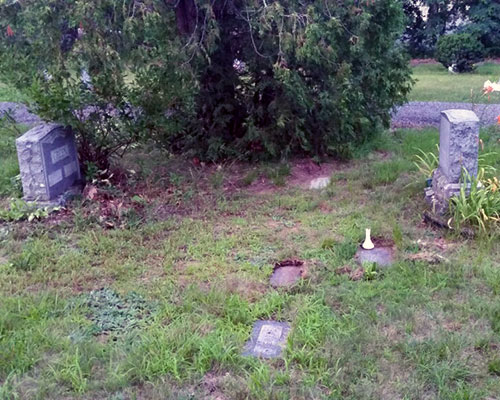

The Green family plot at Greenwood Cemetery, East Broadway.

Evelyn D. (Green) Sullivan’s funeral takes place this afternoon as planned as her family and Greenwood Cemetery reached agreement on her final resting place at Greenwood Cemetery.

Sullivan, who died last Friday night at age 86, will be buried next to her family without the need to cut down any trees or make other alternative arrangements, said Judith Kimball, trustee of the 230-year-old East Broadway cemetery.

“The vault we use is 34 and a half inches wide. So there is plenty of room,” Kimball said.

Sullivan’s daughter, Leslie A. Brown, told WHAV she was “devastated” Saturday when she learned there wasn’t room for her mother at the family’s six-space site. She said she believed a tree had overtaken the family plot and there was room only for a cremation vault—an option her mother would have opposed. Kimball, however, insisted the tree has existed for decades, having been planted by the federal Work Projects Administration (WPA).

While Kimball and Brown disagreed, a compromise was ultimately struck. It calls for using an unoccupied “green space” next to the family plot. Other burials took place at the Green family plot in 1973, 1984, 1987, 1994 and 2010. She said the disputed space was intended for cremains.

Kimball said she succeeded Harry Colby as the sole trustee of the cemetery in 1967. He served for 50 years and she began helping him keep the books in 1960. She said at one time there were several trustees, but they became ineligible to serve. In order to be named a trustee, she explained, a person must own a plot and have paid for perpetual care.

Kimball also disputed a report the owners of a neighboring plot were forced to pay $2,000 to have a private contractor open a grave. She said Greenwood Cemetery actually dug the grave at a cost of only $400.

Finances Tight, But Manageable

Kimball acknowledged money to maintain the cemetery is tight, but the financial situation has actually improved since she took it over. She explained many families couldn’t pay for perpetual care, but were always accommodated.

“Dear Harry Colby. I loved him. He was terrific and he did the job for 50 years. But, Joe Blow would come to him and say, ‘Harry, I can’t afford it.’ And Harry would say, ‘Don’t worry about it. We’ll mow your grave,’” Kimball said. “Even into the 1950s, people were paying $10 a grave,” she added.

When she took over the operation, there was only $37,000 in trust funds, but she was able to build it up to $250,000 at one point. Interest from savings pays for maintenance and her family, owners of Kimball Farm, often chips in with labor and equipment. All lots are mowed even where perpetual care was not purchased, she said.

“It does not get mowed like Linwood does. We don’t have any great, whopping trust funds, any endowments or any of that,” Kimball said. She said she used to mow herself at no charge to the cemetery.

“I mean, for years, I mowed it until one day a man hid behind gravestones and popped out at me. It scared the life out of me because when I’m mowing I don’t have my crutches so I can’t run. I can’t do anything and my husband said, ‘you are no long mowing that cemetery.’”

A single grave now costs $900—“which is quite an improvement over $10 a grave,” Kimball said.