By David Goudsward

Special to Wavelengths

Charlemagne C. Bricault.

When veterinarian Charlemagne C. Bricault died Jan. 10, 1949 at age 82, the obituary in the Haverhill Evening Gazette noted Dr. Bricault’s successful animal practice and his quarter century of work with the city’s health department—first as the inspector of dairies, then as health inspector and finally as a member of the board itself. While Bricault’s prominence as a breeder of Boston terriers was undoubtedly of interest to readers in 1949, the obit did not mention that the good doctor was also a nationally recognized poultryman in his younger days.

In fact, Bricault and his chickens almost single-handedly forced Robert Frost onto the path of becoming an internationally recognized poet.

By the time Bricault moved to Haverhill in 1910, he and Robert Frost had already crossed paths, and each had taken a road less traveled. Bricault was rebuilding his career with the move to Haverhill. His veterinary practice had failed in Andover and his house was in foreclosure. Instead of setting up a new practice immediately, he freelanced at F. C. Newcomb’s Stable on Fleet Street and the Central Club Stable, Central Street, Bradford. After getting a lay of the land, he briefly set up shop at 9 Stage St. before setting up an office at 19 Main St. In 1913, he purchased a home in the Avenues among the farms. His house at the corner of Twelfth Avenue and Main Street would be home to him and his wife Emma for the rest of their lives.

Bricault became Haverhill’s inspector of milk Jan. 1, 1912—a post that evolved over time into inspector of dairies as pasteurization became more prevalent. After a series of disease outbreaks in the mid-1920s that were blamed on raw milk, the position became increasingly important, and Bricault continued to handle the duties himself until his retirement in April, 1939, even as he was still serving on the board of health.

Born in 1866 in Montréal, he received his veterinary degree in from Laval University and an additional degree from the Ecole de Médecine Vétérinaire de Montréal. He arrived in Lawrence in 1892 and lived with his brothers, one of only two veterinarians in Lawrence. In 1895, he purchased a farm on Pleasant Street in Methuen near Marston’s Corner. The veterinary business had not met his expectations and, with a family to consider, he wanted to get out of the city. This new property gave him room for another business—a poultry farm.

Enter Robert Frost

Robert Frost in 1910.

Robert Frost was living in Lawrence in the spring of 1899, having been forced to withdraw from Harvard because of a stress-induced illness. But the symptoms were getting worse, not better. His doctor told him it could be a nervous condition or it could be consumption. In either case, a prescription would not resolve the issue, he was advised to break out of his sedentary lifestyle and get some exercise, preferably outside in the fresh air. He suggested farming. Frost, having failed miserably as a farmhand previously in Salem and Windham, N.H, couldn’t bear the thought of such drudgery again.

Walking to clear his head and come up with a more promising solution, he wandered up Prospect Street into Methuen. Near the Merrill School, where his mother had once taught, Frost noticed a house with a series of chicken coops in a neighboring field. It reminded him of his childhood in San Francisco, where he had a kept a few baby chicks. He decided it would be less tedious to raise chickens than to run a farm. He went to the house to ask advice. And that was how Frost met Bricault.

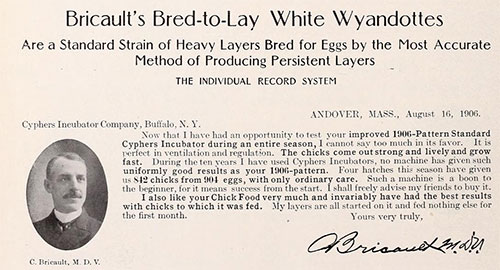

Bricault was glad to meet a potential customer and took him on a tour of the operation. The coops contained pedigreed chicken: Barred Plymouth Rocks, which he was phasing out, and White Wyandottes. Bricault was not just raising chickens for the eggs and local butchers, he was developing a better chicken. He was carefully monitoring which chickens produced the most eggs, then bred those birds to pass the trait along, theoretically increasing productivity. He advertised his farm as home to “Bred-To-Lay” chickens that produced “Layers Bred from Layers,” and claimed he had chickens that produced 200 eggs a year—an unheard of number.

Frost was convinced and was also able to convince his grandfather to underwrite the project. A house was rented on Pleasant Street, about a mile from Bricault’s farm. Bricault explained the best methods for setting up a poultry farm, made recommendations for incubators and feed and sold him the incubator eggs to begin. More importantly, Bricault promised he would help find a market for Frost’s eggs and poultry.

Frost’s health improved as the chicks became pullets and began laying egg in the fall. Bricault continued to buy eggs and chickens—the purchases from Frost allowed him to continue to provide eggs and roasters to his customers even as he was cutting back on his poultry operation because of increasing demands from his veterinary practice. More than one of Frost’s biographers suggest that the two were functioning as an impromptu partnership by this time.

Frost had so many chickens on the property by the next year, the landlady suggested they needed a larger space, and insisted they relocate (being months behind in the rent was probably also a factor). In October, Frost, his wife, his daughter and 300 White Wyandotte chickens made the move to Derry, N.H. Today, the farm that remains safely preserved by New Hampshire as the Robert Frost Farm State Historic Site.

Bricault briefly moved to Vermont in 1900 to manage a large poultry farm, but disliked not being a sole proprietor. Having leased out his Methuen farm, he bought a new farm in Andover. Starting his flock from scratch, he continued to rely on Frost’s poultry, but he never seemed to regain momentum. There wasn’t sufficient time to do the breeding program for his “Layers Bred to Layers” program and deal with his veterinary office, which was not flourishing in Andover. Finally in 1905, Bricault abandoned the poultry business.

In Derry, Bricault’s decision had far-reaching consequences. Frost discovered he did not have the time or inclination to peddle eggs himself, and he never was comfortable butchering the birds. The few products he could sell were at a price significantly lower than that Bricault had been offering. Bricault’s reputation had allowed him to charge a higher retail price, which allowed him to pay Frost a better price. Bricault had effectively subsidized Frost’s poultry business through the inflated prices he paid for eggs.

It didn’t take Frost long to see the writing on the wall. The farm was no longer profitable enough to live on unassisted. He needed a paying job to supplement income. Frost decided to try teaching. Having had assisted his mother at her private school, he felt he had enough experience to at least make inquiries. He approached Reverend Charles Loveland Merriam, a trustee of the local Pinkerton Academy, two miles away from the farm.

In 1906, Frost began teaching sophomore English at Pinkerton. With more discretionary time in his schedule, the poems he had scribbled down in fleeting moments at night became part of his daytime activities. He soon began to gather a reputation as more poems saw publication.

Bricault’s decision to abandon poultry farming turned out to be a bad decision for the veterinarian. He was forced to close his practice within four years, when he moved to Haverhill. For Frost, though, the removal for poultry farming from his life would be the catalyst for a career in literature that would win him four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry, a Congressional Gold Medal and his 1958 appointment as poet laureate of the United States.

Frost never forgot Bricault. In 1963, the Christian Science Monitor quoted the poet.

“I sold my eggs to a man who bred White Wyandottes. For a while I was fairly well off until he went out of business. He became a horse doctor in Haverhill.”

David Goudsward, raised on the summit of Scotland Hill, brings his New England sensibilities and respect for historical perspective his work. Although living in Florida, his bibliography consists primarily of New England topics. His latest book, “Horror Guide to Massachusetts,” is available via Amazon. He is WHAV’s Open Mike Show’s historian.

This program is supported in part by a grant from the Haverhill Cultural Council, a local agency which is supported by the Massachusetts Cultural Council, a state agency.